Sokratis Papadopoulos data | urban | policy

A new method to grade buildings on energy performance

As the discussion on the effects of anthropogenic climate change builds up, local and federal governments worldwide are designing policies to “green” existing building stocks. Recently, New York City enacted a law mandating large building owners to publicly display their energy performance grades, as a means to increase the appreciation of sustainability in the real estate market and promote energy efficiency investments.

These grades will be calculated based on Energy Star, the predominant energy benchmarking methodology in the US. My latest paper shows that grading buildings on energy performance is a complex problem and how Energy Star method’s simplicity is not sufficient to address it. Having identified the limitations of Energy Star, we go one step further and propose a new grading methodology leveraging machine learning and city-benchmarking energy data to reduce uncertainty.

The limitations of Energy Star

Model complexity - Energy Star is based on a linear regression model. However, the relationship between energy consumption and its predictors in many cases is found to be non-linear.

Data quality - The data used to train the model come with two major issues. First, the dataset is a nationwide sample, not accounting for spatial variations. In a previous paper, we show that the relationship between features, such as age or gross floor area, and building energy consumption varies across different geographic regions. Second, the model is trained on small data samples. Specifically, for the residential building model that we analyze below, Energy Star is fitted on 322 examples, whereas the benchmarking policies of NYC only have resulted to more than 7,500 reported properties.

Limited features - The model accounts for five features, neglecting important physical, operational, and qualitative aspects associated with energy consumption.

The need for a paradigm shift

In order for a energy performance grading scheme to be accepted by the market and society, it should meet several criteria:

- Must be understood by the various stakeholders; in the sense of being clear why a certain building is receiving a certain grade and what changes need to be made to move from one grade band to another.

- Must account for a multitude of characteristics, focusing on the ones that can be readily changed.

- Must be scalable and generalizable so that it can be deployed across a range of climate and market-specific conditions.

- Difference in grade bands must be distinct with a high degree of confidence.

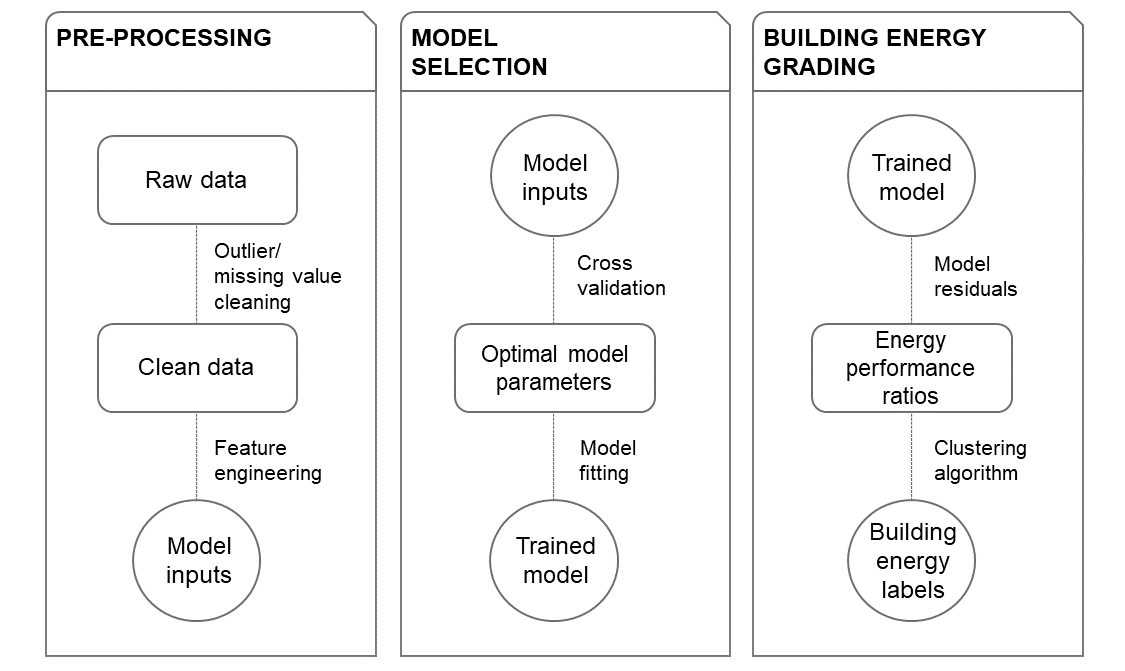

With these four points in mind we develop the GREEN index, a city-specific energy performance grading system. We use XGBoost, a non-linear ensemble learning algorithm, to model the data, and K-Means to cluster the model residuals and assign grades to individual buildings. The magnitude of the residuals essentially describes the deviation of the actual building energy performance from the idealized (model-based) one, and this is what we define as a measure of performance.

The findings

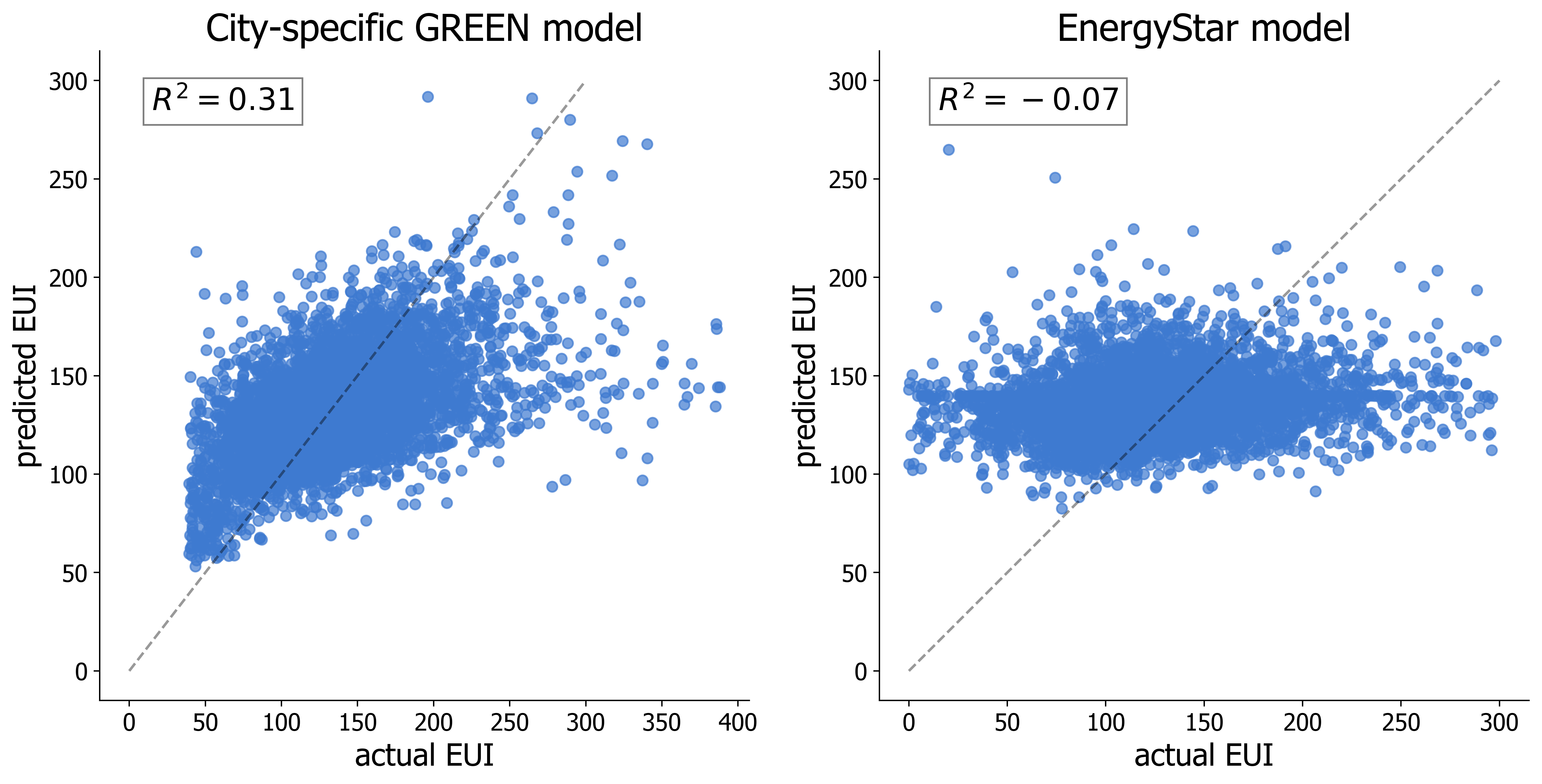

When we fit our GREEN model on NYC data and compare it with its equivalent Energy Star, we are not surprised by the results.

See how Energy Star is not capable of explaining any of the variance in the data. Practically, predicting energy use intensity using this model is no better than a “naive” model which always predicts the dataset’s mean. On the other hand, our model explains more than 30% of the variability in the data. The rest of the variance is attributed to features that our model doesn’t (and shouldn’t) capture, such as occupant behavior and building systems’ quality.

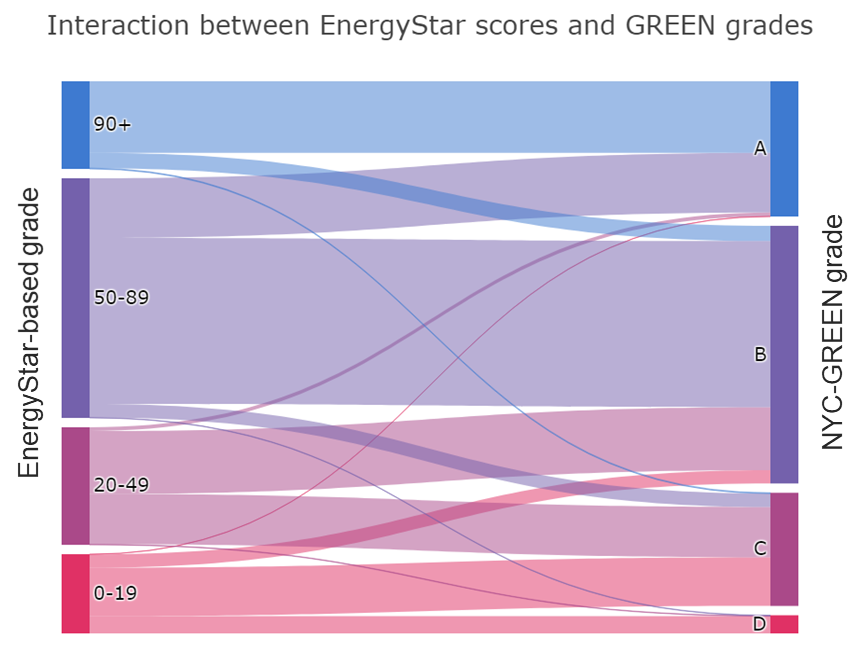

In the Sankey diagram below we show the interactions between our grades for NYC and the Energy Star-based scheme that was recently adopted by the City. We show that more than 40% of the properties analyzed receive different grades under the two grading schemes. In some cases we even see buildings receiving “A” under the NYC-GREEN, while their Energy Star grade being “C” or “D”.

Final thoughts

Although climate action by cities is a vivid topic of discussion, the use of data-driven solutions for market transformation is still in its nascent stage. Public-facing energy performance grades can be a effective peer-pressure mechanism to motivate energy efficiency actions and investments; however transparency, fairness, and robustness should be key elements if we want the society to adopt such grades.

Moreover, cities should start promoting market-specific and contextualized metrics to address not only energy, but any urban challenge they might face. Given the abundance of data and the unique characteristics of each city, local governments might need to come up with bottom-up solutions that compliment federal policies.

For more details, you can read the full paper and check the project code repository.

Written on October 24th, 2018 by Sokratis Papadopoulos